“Chess, like love, has the power to make men happy,” wrote the great Siegbert Tarrasch. To most people, his name means nothing today, but among chess players he is recognized as one of the great ones who, however, was never world champion. Chess has made me happy for most of my life, although I must also confess that it is an obsession, even an addiction that I’ve tried to give up several times. Chess can suck up life like no other human activity. To most people, it is just a game played by old men in extreme slow motion, about as interesting as watching paint dry. For the players, however, there is furious activity going on in the mind, as they race the clock (yes, there is nearly always a clock present) and try to calculate possibilities, and the ramifications resulting from any sequence of moves. For serious players, chess is a struggle combining elements of various sports and art, and difficult to explain to non-players.

I learned to play chess by watching my cousin Jack, a returnee from Auschwitz, playing with his business partner during lunch hours, in Brussels, when I was about ten years old. Both of them were rather surprised when I began suggesting moves, doing what is called “kibitzing” their games, which they didn’t really appreciate. Chess didn’t become an obsession for me until high school, when I began to move into the world, the culture of chess players, a world in which all shared my addiction. I had given up chess while doing my military service, but it didn’t take me long to resume my bad old habits once I returned to civilian life. It was a small world inhabited by some famous players who were all known to each other at least by reputation. In Manhattan they played in one of three or four venues, the most important being the Manhattan Chess Club, which being financially strapped had to move from time to time.

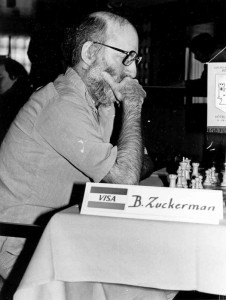

On Sunday mornings, I played at the Manhattan Chess Club. I couldn’t afford the membership fee, but that was not unusual for a chess player. The club was rather lax about enforcing membership rules, which might have been the reason it was always in financial trouble. As I watched another game, a young man came into the room and asked me if I wanted to play, and we began a game which I won, and then we played another nine games, always from the same opening moves, and I won all of them. At the end of the session, the young man, who was just a teenager in those days, introduced himself as Bernard Zuckerman, and I introduced myself as Raskolnikov. After that he left, but he reappeared for several Sundays to play with me, each time making my win margin smaller. After the fourth week, I could no longer win a single game against him. He was slated to become one of the strongest players in the country. As a matter of fact, several years later, I saw him when he was playing for the US Chess Championship in a hotel on Lincoln Square in which both Bernard and Bobby Fisher were competing, and which Fisher won without the loss of a single game. Between moves, as Bernard noticed me sitting in the crowd, he walked off the stage, came over to me and asked, “Your name isn’t really Raskolnikov, is it?” I guess he had read Dostoyevsky by that time.