Meanwhile, while attending school and working at Figaro, I was living on St. Mark’s place, less than a block from Tompkins Square Park, which is located between Avenues A and B. At the time, Tompkins Square Park was one of the more neglected parks in the city, although it was home to a modest monument, a fountain, commemorating the greatest disaster to strike New York up to September 11,

2001. On June 15th, 1904, the General Slocum, an excursion paddle-wheel boat carrying over 1,300 passengers, mostly German women and children from the St. Mark’s Lutheran Church (on St.Mark’s Place, in the neighborhood then known as “Little Germany”), caught fire while steaming on the East River. Instead of returning to the nearby shore, the captain kept her going while on fire for another three miles. The life jackets, which had been made of cork, had deteriorated to the point of just being dust. 1021 of the 1342 passengers died in the fire or perished trying to escape it, jumping into the river most often drowning when dragged down by vicious currents and their bulky dresses. Today this disaster is just about forgotten by most New Yorkers, except by surviving relatives of those who died or the people who bother reading the inscription on the monument in Tompkins Square Park.

When I moved to St. Mark’s Place, I had made some new friends. One of them was my neighbor, Sam Praeger, a painter, who had arrived from someplace in the Mid-West. Each of us had a storefront, and he had set up his “atelier” in the front room of his, although he lived in the back. Each of our “apartments” had a front room with a large window facing the street (after all, they were former stores), a bedroom, and a kitchen in the back with a covered claw footed bathtub, and a closeted toilet. We also had a little garden way back. The cover of the bathtub could serve as a table which was often handy. We shared a common hallway. This was not an unusual arrangement for these tenements that had been built in the last half of the 19th Century. Sam described himself as an “action painter,” although I’m not quite sure what that meant. I think it had something to do with painting figures in mid motion in a vaguely cubistic style. He liked to paint really big canvases, and according to him, the only place to sell paintings that large was New York. He particularly liked to paint bulls and bullfighters, just at the moment most unpleasant for the bull.

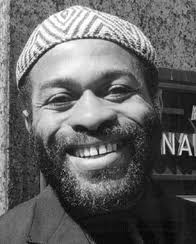

This kind of specializing in a painter didn’t surprise me, as earlier, Ted Joans, another friend of mine, who went on to achieve minor fame as a Beat poet, liked to paint rhinoceroses, with particular attention to their knees and horns. Ted had been a jazz musician when he arrived from Chicago, and had then switched to painting, after which he organized really neat, parties at his loft that “guests” paid to attend. He really was into rhinoceroses, but when he heard that there was money to be made reading poetry in coffee houses, he switched muses and became a well-known poet. So, Sam Praeger liked to paint bullfighters and bulls, but this was no impediment to our friendship. We got along splendidly. He introduced me to a friend of his, William, who was a teacher at Cooper Union, the man who was about to get me involved in my next project, a venture into theater.

Well, I didn’t know any of this. And I bet you didn’t know that my Spanish family includes a former bullfighter and a collection of rhinoceros art. I kid you not!

and I’ll throw in a plug for my in-laws gallery — the logo is in fact a rhinoceros.

http://www.frame.es/