Each year, George Washington High School, whose total enrolment was about 4,000 students, admitted nearly a thousand students “over the counter,” which meant that they were most often kids straight from Santo Domingo and parts thereabouts. They spoke only Spanish, and often could not read in their own language. Of course, when we gave reading and math tests, our students “underperformed” and did so spectacularly. We could have told the Board of Education that, without all the money wasted on testing. And of course, as far as the Board of Ed and the New York Times were concerned, these kids “underperformed” not because they spoke no English, but because of bad teaching.

As our students learned English, these Dominican students were shuffled into regular English classes, and some did remarkably well, much like previous generations of immigrants had done, while many did not. It is much easier to teach English speaking middle class students than it is to teach the poor and the foreign born.

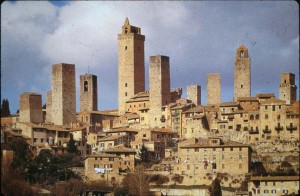

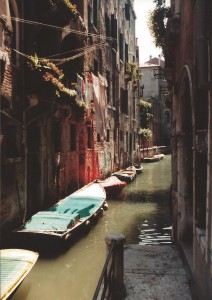

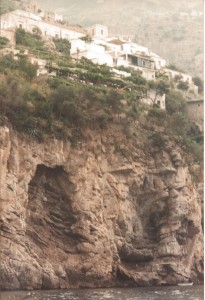

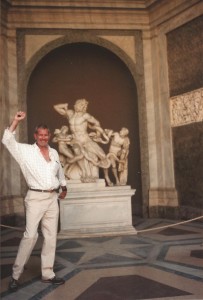

The year I came back from Italy, I was assigned the worst senior English class in the school, a fearsome assignment entailing involvement with guidance personnel, probation officers and more than average difficult students. The first day I entered my noisy and crowded classroom of 35 students, I saw a large young man sitting at my desk. When he stood up, he was almost as tall as I was, and I was 6’3″. He was well muscled and goateed, and wore a cut off T-shirt with the simple motto, “Fuck Everybody”. To my surprise, when I asked him to go to his own desk, he did. It was then that the idea struck me to do something that had never been done in any classroom in any slum neighborhood school in the city. I didn’t know, and I didn’t care if it had any educational value, but I was going to do it anyway.

First I told the class that I liked a friendly greeting when I walked into a classroom, and to that end I would teach them the greeting I expected each morning, when I entered the room. It was, “Good morning, teacher kind and true. A happy day we wish to you,” which they learned rather quickly. I made the goateed T-shirt, whose name was Pedro, my class president, and it was his responsibility to lead the choral speaking when I walked through the door each morning. My students immediately saw the humor in the situation, and each morning as I walked into my classroom, these refugees from the probation office stood up, the class president moved to the front of the class and led the recitation of an enthusiastic, “Good morning, teacher kind and true. A happy day we wish to you!” After that, those kids were mine, and I was able to teach whatever I chose without any trouble whatsoever.

This didn’t last beyond the first day I was out sick. A substitute teacher panicked when my class president moved to the front of the class and led the class in the formal greeting they had been taught. She ran out of the classroom, right to the principal’s office, and complained about this large student who had taken over the classroom in a loud and boisterous manner. When I came back to school the following day, the principal asked for an explanation, which I gave him, but I was forbidden to do anything like that with my students again. It was fun while it lasted.