Periodically we had our beds “tossed”. This meant that our blankets and sheet were ripped off our beds and the mattresses were turned over in a search for contraband items, items such as alcohol or weapons. These searches were carried on when we were busy working elsewhere and none of us worried about them, as we had none of these forbidden items. On the part of the authorities these searches were more-or-less just pro forma. However, one of these searches was considerably more than that for me.

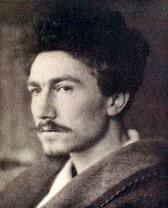

One day, after returning from the stockade mess hall, I was told to report to Sergeant Prager’s office immediately. Because this was so unusual, I expected the worst, most likely big trouble and prepared myself mentally for my first stay in the Box, although I had no idea why. When I entered his office, Provost Sergeant Prager was at his desk. He looked me over as I stood at attention. He pointed to a notebook on his desk and asked me, “Is this yours?” I looked at the notebook and immediately recognized it. It was the notebook in which I kept my notes on everything that was happening to me in the Army, including my trial and my life in the stockade. It was going to form the basis of the Great American Novel which I planned to write as soon as I was out of the Army, and I considered it my most valuable possession. “Yes, sir!” I replied. “That’s mine, sir!” seeing no reason to deny my ownership. Sergeant Prager again looked at me, and said, “Do you know it is forbidden to keep notes on what happens in our stockade?” “No, sir,” I said, “I do not.” He then asked me a question which was one of the most surprising and unexpected of my life, namely, “Have you heard of Ezra Pound?” Of course I had heard of Ezra Pound, but I didn’t expect Prager to have heard of him. “Yes, sir!” I replied. “Do you know what they did to Pound when they found him writing in jail in Italy?” I was forced to admit that I had no idea what was done to Pound when he was caught writing in Italy. “No, sir! I don’t” “Well,” said Prager, “They clapped him into solitary confinement for six months.” This was an exaggeration, of course, but then who had expected the Sergeant to be an expert on the life of Ezra Pound? And I wasn’t really in a position to debate Pound’s jail experience for treason with Prager. He looked at me, probably to see what effect his words had had on me, and to tell the truth, the effect was considerable. I was scared shitless. I could see myself in the Box not only for the regular two weeks, but for the foreseeable future. He then continued, “Your stuff isn’t as good as Pound’s; so I’m not going to bother sticking you in the Box. But don’t let it happen again. I’m confiscating this,” pointing to the notebook. “Dismissed!” I turned around, gratefully walked back to my bunk, and was careful never to write anything else while in the stockade.

Wow. Very lucky for you.

In chess we say, “Better to be lucky than smart.”